With the rising of cloud technologies, companies had a chance to create, deploy and manage their applications without paying upfront. In the old days, you need to buy some rack, network cables, servers, coolers, etc. It was taking too much time, and generally, huge tech companies took advantage of their vendor-locking technology stacks. You didn’t have much choice, right? With the free software movement and foundations like CNCF, standardization of the technologies becomes much more important. Nobody wants vendor-locking because it kills disruptive ideas.

Then suddenly Docker became popular(or is it?) and companies realized they don’t need to use the same stack for every problem with containerization technologies. You can choose your programming language, database, caching mechanisms, etc. If it works once, it works every time. Right? We all know it is not true. Distributed systems give us scalability, agility, availability, and all of the other good advantages. But what was the price for it? Operational costs and bigger complexity problems. You can run your container with whatever you want but in the end, you have a much more complex system than ever. How can you trace, monitor, and gets logs from every container? How about authentication, authorization, secret management, traffic management, and access control?

Those problems created solutions like Kubernetes. With this blog post and simple template project, we can learn more about Kubernetes deployments. It is a huge area to explore but I think deployments are a great place to start. At the end of the day, you need to enter this world with just a simple deployment. Kubernetes is generally used for companies that are using microservices and none of them changed their infrastructure in a day. They all started with a simple deployment. You don’t need to think about tracing, monitoring, secret management, etc. Don’t worry. Kubernetes will lead you to these problems. Focus on them one at a time.

Before reading the rest of the post, be sure that you have an idea about Kubernetes components and how they are working with each other. I am just gonna focus on the deployment side of the Kubernetes.

Motivation Link to heading

I can’t write every single aspect of Deployments in a simple blog post. My goal is to give you a simple template project that you can use for your projects. I am gonna explain the template project in detail. You can use it as a reference for your projects. Don’t worry there will be lots of tips and tricks along the way. Also, I’m gonna keep updating the project with new features.

Demo Requirements: Link to heading

- Check template project. It can be slightly different from blog post.

- Docker

- Kind

- Helm

Clone template project.

git clone https://github.com/fatihkc/ultimate-k8s-deployment-guide.git

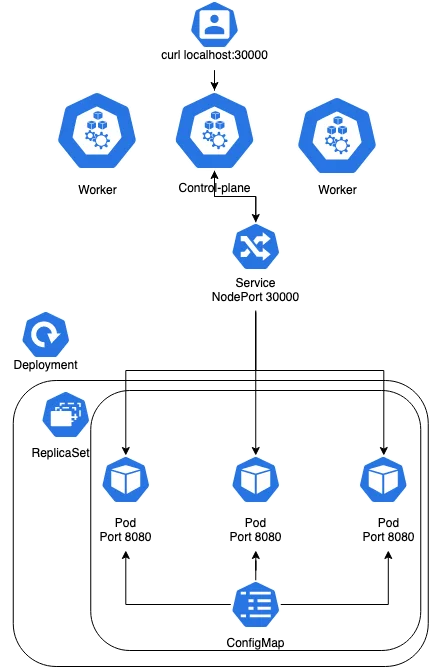

Diagram Link to heading

Kind Link to heading

Kind is a great tool for creating Kubernetes clusters without losing time. Normally you need virtual machines for installation but Kind is using containers as virtual machines. That is brilliant technology. Simple to use, need much fewer resources, and is fast. You can also use it for testing different Kubernetes versions and checking if your application is ready for an upgrade or not. You can always choose hard way. It is really good for understanding what is going on with your cluster. 3 years ago I was installing Kubernetes with Ansible and Vagrant. Check this project if you want to know more about it.

kind create cluster --config kind/cluster.yaml --name guide --image=kindest/node:v1.23.6

Helm Link to heading

Helm is a package manager for Kubernetes applications. If you are new to Helm, I don’t recommend creating a default template(helm create chart). Because it is more complicated than it needs to be. I am gonna write about important things for deployments and explain them one by one. Let’s start with our Chart.yaml file.

apiVersion: v2

name: helm-chart

description: A Helm chart for Kubernetes

type: application

version: 0.1.0

appVersion: "1.0.0"

All you need to focus on is the version and appVersion field. Why do we have two different version variables? Let’s say you have an application that runs with 1.0.0. You can increase it via semantic versioning tools and then pass it to the Helm chart. I recommend increasing the chart version is very important for this scenario. Also using appVersion for your image version tag is recommended. But you can update your chart without increasing the application version too. You can add or create new YAML files, and make improvements and appVersion can stay the same. Then you should only increase the version variable.

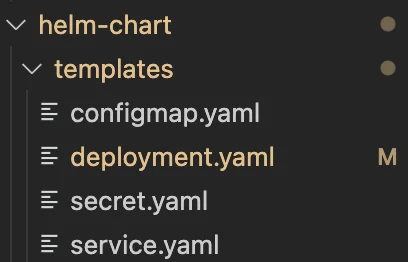

Templates Link to heading

Templates are your YAML files that use to create Kubernetes resources. The important thing is to divide them by their resource type and name them resource-type.yaml. Let’s create a simple deployment and check what they are using for.

Deployment Link to heading

apiVersion: apps/v1 # API version to use for all resources in the manifest

kind: Deployment # Kind of the resource to create

metadata:

name: {{ .Release.Name }} # Name of the resource to create

namespace: {{ .Release.Namespace }} # Namespace of the resource to create

labels:

app: {{ .Values.deployment.name }} # Label to apply to the resource

spec:

replicas: {{ .Values.deployment.replicas }} # Number of replicas to create

selector:

matchLabels:

app: {{ .Values.deployment.name }} # Label to select the resource

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: {{ .Values.deployment.name }} # Label to apply to the resource

spec:

containers:

- name: {{ .Values.deployment.container.name }} # Name of the container in the pod

image: {{ .Values.deployment.container.image }} # Image to use for the container

imagePullPolicy: {{ .Values.deployment.container.imagePullPolicy }} # Image pull policy to use for the container

ports:

- containerPort: {{ .Values.deployment.container.port }} # Port to expose on the container

protocol: {{ .Values.deployment.container.protocol }} # Protocol to use for the port

This might look a little bit complicated. How do we know where to write these keywords? There is two spec, multiple labels, and so many brackets. Well, you just need to check the documentation and learn how to read a YAML file. YAML files are all about spaces and keywords. As you can see, we say that I need to use apps/v1 API for my Deployment kind of resource. Kubernetes is just a big API server. Don’t forget that. There are many API’s in Kubernetes. Check them with;

kubectl api-version

kubectl api-resources

Then we give a name to the resource. Some people use names like “ReleaseName-deployment” but I prefer keeping it the same with the release name. Deployment is responsible for running multiple containers so we choose how many replicas we want. Selectors using for finding which pods we are gonna manage with Deployment. In the background, a Replica Set will be created it will be responsible for running the pods. If you are not familiar with Replica Sets, check this article.

Then we gave information about our containers. I only have one but it is enough for now. You can declare more containers in a pod.

Values Link to heading

What about the values that are all over the deployment.yaml? Well, they are saving so much time and you can able to use different values files for different environment files. You use most of the things as values and easily change them with values.yaml file. Like cluster.yaml for Kind. You can use them with {{ .Values.deployment.name }}. Just check values.yaml file.

Deployment strategy Link to heading

Deployment strategy is a way to control how many replicas are created. You can use different strategies for different deployments. I prefer RollingUpdate for seamless upgrades.

strategy:

type: RollingUpdate # Type of the deployment strategy

rollingUpdate:

maxSurge: {{ .Values.deployment.strategy.rollingUpdate.maxSurge }} # Maximum number of pods to create

maxUnavailable: {{ .Values.deployment.strategy.rollingUpdate.maxUnavailable }} # Maximum number of pods to delete

Environment variables Link to heading

Environment variables are used to pass information to the containers. You can use them in your containers with $VARIABLE_NAME. I am using it for changing the USER variable. It will affect my application output.

env:

- name: USER

value: {{ .Values.deployment.env.USER }} # Value of the environment variable

ConfigMap Link to heading

ConfigMap and environment variables are very similar. The only difference is when you change your environment variables changes, the pods are gonna restart and then take the new value. But ConfigMap is not gonna restart your pod. You need to restart it manually. If your application can handle it, it is a good idea to use ConfigMap.

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: {{ .Release.Name }}

namespace: {{ .Release.Namespace }}

data:

USER: "{{ .Values.USER }}"

Secrets and Volumes Link to heading

volumeMounts:

- mountPath: "/tmp" # Mount path for the container

name: test-volume # Name of the volume mount

readOnly: true # Whether the volume is read-only

volumes:

- name: test-volume # Name of the volume

secret: # Volume to use for the secret

secretName: test # Name of the secret to use for the volume

Secrets are very similar to environment variables with small differences. If your variable contains sensitive information like database passwords and credential files for third-party services, you can use secrets. All of your YAML files are stored in etcd but secrets are encrypted. ConfigMaps are not encrypted. When you list your secret in Kubernetes you will see it is base64 encoded. You can use base64 decode to get the original value. So where is encryption and why does base64 encode? Let’s say your application uses credential files like Firebase. It has multiple lines with different syntax than just a simple password. Encoding it keeps the spaces and new lines. If you want to completely hide your secret, you can use solutions like Hashicorp Vault.

I could use it like ConfigMap but I prefer using volumes. Because your application logs can show your environment variables like secrets. If you prefer volumes, it is a long shot to expose secrets. If you have a configuration file, then it will be the perfect fit. You don’t use volume as your main storage. Instead, use persistent volumes. It is a really deep dive, just check this article. One last thing, don’t use secret.yaml like me. It is not a good practice. Don’t keep it in your repository. You can use it as a template and create it with Helm.

$ k exec -it webserver-5d7d6ccc8d-l8ftz cat /tmp/secret-file.txt

top secret

Container resources Link to heading

resources:

requests:

cpu: {{ .Values.deployment.container.resources.requests.cpu }} # CPU to request for the container

memory: {{ .Values.deployment.container.resources.requests.memory }} # Memory to request for the container

limits:

cpu: {{ .Values.deployment.container.resources.limits.cpu }} # CPU to limit for the container

memory: {{ .Values.deployment.container.resources.limits.memory }} # Memory to limit for the container

This part is a little bit tricky. Kube-scheduler is responsible for a simple decision. Which pod, which node? If you have a request for a pod, make sure that you will have enough CPU and memory in a node. It allocates your requests. You can use much more resources in a node but minimums are clear for kube-scheduler. Limits are responsible for top usage. Do you need them? If you are not an expert in this area, simply no. Because in a high traffic situation where pods need more resources, you are limiting it and that means not giving a response to high demand. We don’t want that right? Unless you have a different situation with your infrastructure. I am gonna use it for demo purposes. Use metrics-server for monitoring your pod’s usage.

Health probes Link to heading

livenessProbe:

httpGet:

path: {{ .Values.deployment.container.livenessProbe.path}} # Path to check for liveness

port: {{ .Values.deployment.container.livenessProbe.port }} # Port to check for liveness

initialDelaySeconds: {{ .Values.deployment.container.livenessProbe.initialDelaySeconds }} # Initial delay before liveness check

timeoutSeconds: {{ .Values.deployment.container.livenessProbe.timeoutSeconds }} # Timeout before liveness check

readinessProbe:

httpGet:

path: {{ .Values.deployment.container.readinessProbe.path }} # Path to check for readiness

port: {{ .Values.deployment.container.readinessProbe.port }} # Port to check for readiness

initialDelaySeconds: {{ .Values.deployment.container.readinessProbe.initialDelaySeconds }} # Initial delay before readiness check

timeoutSeconds: {{ .Values.deployment.container.readinessProbe.timeoutSeconds }} # Timeout before readiness check

Health probes are really important for the availability of your application. You don’t want to send a request to the failed pod, right? Liveness probes are used for understanding whether or not your pod can accept traffic. If it fails, it kills the pod and restarts it. Let’s say it is ready for accepting connections. But is it ready for action? Readiness probes are used for checking third-party dependencies. Can you reach the database? Is another related service alive or not? Can pod achieve its job?

Liveness probes must be simple like sending a ping. On the other hand, readiness probes must be sure that they can accept traffic. Otherwise, other ready pods will handle the traffic. A piece of advice, don’t check third-party dependencies in liveness because it can kill all of your applications. Check this awesome article about health probes. These probes are not coming out of the box, unfortunately. Your application code must handle them by exposing the application’s health status. We have HTTP health probes. What about gRPC connections? Well, that’s another adventure to discover.

Security Context Link to heading

securityContext:

allowPrivilegeEscalation: false

readOnlyRootFilesystem: true

runAsNonRoot: true

runAsUser: 1000

capabilities:

drop:

- ALL

The security context is one of the most important things about deployment. This mechanism is changing with the new Kubernetes releases but the idea is still the same. Do you want to allow privilege escalation? No. Read-only filesystem? Hell yeah. And more things like that. Don’t forget to drop all capabilities. Check out documentation about security contexts.

Affinity Link to heading

affinity:

nodeAffinity:

preferredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution:

- weight: 10 # Weight of the node affinity

preference:

matchExpressions:

- key: kubernetes.io/arch # Key of the node affinity

operator: In # Operator to use for the node affinity

values:

- arm64 # Value of the node affinity

- weight: 10 # Weight of the node affinity

preference:

matchExpressions:

- key: kubernetes.io/os # Key of the node affinity

operator: In # Operator to use for the node affinity

values:

- linux # Value of the node affinity

Affinity is really good for large environments. You can have different types of nodes. They can have different architecture, operating systems, sizes, etc. For example, I’m using an affinity for Karpenter. Karpenter allows you to scale out within 60 seconds. If your pod needs resources and can’t find them, Karpenter creates a new node and assign your pod. I’m using EC2 Spot instances for this purpose. You just need to choose your deployments and make them scalable with Karpenter. Affinity is making sure that this pod will run on the nodes that have required labels. In our example, I used architecture and operating system but If you have solutions like Karpenter, It becomes much more important.

Topology Spread Constraints Link to heading

topologySpreadConstraints:

- maxSkew: 1 # Maximum number of pods to spread

topologyKey: "topology.kubernetes.io/zone" # Key to use for spreading

whenUnsatisfiable: ScheduleAnyway # Action to take if the constraint is not satisfied

labelSelector:

matchLabels:

app: {{ .Release.Name }} # Label to select the resource

- maxSkew: 1

topologyKey: "kubernetes.io/hostname" # Key to use for spreading

whenUnsatisfiable: ScheduleAnyway # Action to take if the constraint is not satisfied

labelSelector:

matchLabels:

app: {{ .Release.Name }} # Label to select the resource

Now we are sure that our application will run on arm64 architecture with Linux operating system. What if all of our pods run on the same node? If that node is terminated then our application will not available. We must spread them. Topology spread constraints allow us to make sure our pod will run on different hosts, zone, or any other topology. For demo purposes I only chose hostname.

Service Link to heading

Service is a Kubernetes resource that allows you to expose your application. It is a load balancer for your pods. You can use it for internal or external traffic. I choose NodePort for my service. It is a simple way to expose your application. You can use it for testing purposes. It exposes a port on each node. You can access your application with the node’s IP address and the port.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: {{ .Release.Name }} # Name of the service

namespace: {{ .Release.Namespace }} # Namespace of the service

spec:

type: NodePort

selector:

app: {{ .Values.service.selector.name }}

ports:

- protocol: {{ .Values.service.ports.protocol }}

port: {{ .Values.service.ports.port }}

targetPort: {{ .Values.service.ports.targetPort }}

nodePort: {{ .Values.service.ports.nodePort }}

Action Link to heading

Now we are ready to deploy our application. We have a chart and resource templates. We can use the helm install command for that.

helm upgrade --install webserver helm-chart -f helm-chart/values.yaml -n $NAMESPACE

I generally use “upgrade –install” commands instead of “install” because I can use the same command for updating my application. If anything is missing, it will install it. If something changed, it will update it. Let’s check our resources.

kubectl get all -n $NAMESPACE

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE IP NODE NOMINATED NODE READINESS GATES

pod/webserver-5d7d6ccc8d-l8ftz 1/1 Running 0 83m 10.244.1.11 guide-worker <none> <none>

pod/webserver-5d7d6ccc8d-ncdxq 1/1 Running 0 83m 10.244.2.7 guide-worker2 <none> <none>

pod/webserver-5d7d6ccc8d-xpljk 1/1 Running 0 82m 10.244.1.13 guide-worker <none> <none>

NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE SELECTOR

service/kubernetes ClusterIP 10.96.0.1 <none> 443/TCP 46h <none>

service/webserver NodePort 10.96.29.110 <none> 8080:30000/TCP 23h app=webserver

NAME READY UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGE CONTAINERS IMAGES SELECTOR

deployment.apps/webserver 3/3 3 3 23h webserver fatihkoc/app:latest app=webserver

NAME DESIRED CURRENT READY AGE CONTAINERS IMAGES SELECTOR

replicaset.apps/webserver-5d7d6ccc8d 3 3 3 83m webserver fatihkoc/app:latest app=webserver,pod-template-hash=5d7d6ccc8d

replicaset.apps/webserver-68667fc8c7 0 0 0 23h webserver fatihkoc/app:latest app=webserver,pod-template-hash=68667fc8c7

replicaset.apps/webserver-689c788945 0 0 0 23h webserver fatihkoc/app:latest app=webserver,pod-template-hash=689c788945

Everything looks ready. Let’s access our app and see how it works.

curl http://localhost:30000

Hello, Fatih! Your secret is: top secret

You might think why I used port 30000. Well, the easiest way to access your application is to use NodePort. You can use LoadBalancer or Ingress but I don’t want to make it complicated. In Kind configuration, I exposed port 8080 to 30000. You can change it on your own.

Conclusion Link to heading

In this blog post, we checked most of the components about Deployment. Of course, there are tons of things to learn. I tried to make it simple and easy to understand. I hope you enjoyed it. If you have any questions, feel free to ask.